theological triage: a foundational concept

how do we know what Christian doctrines, beliefs, and disagreements are the most important?

This post is second in a series on studying theology through the creeds. Read the first post here.

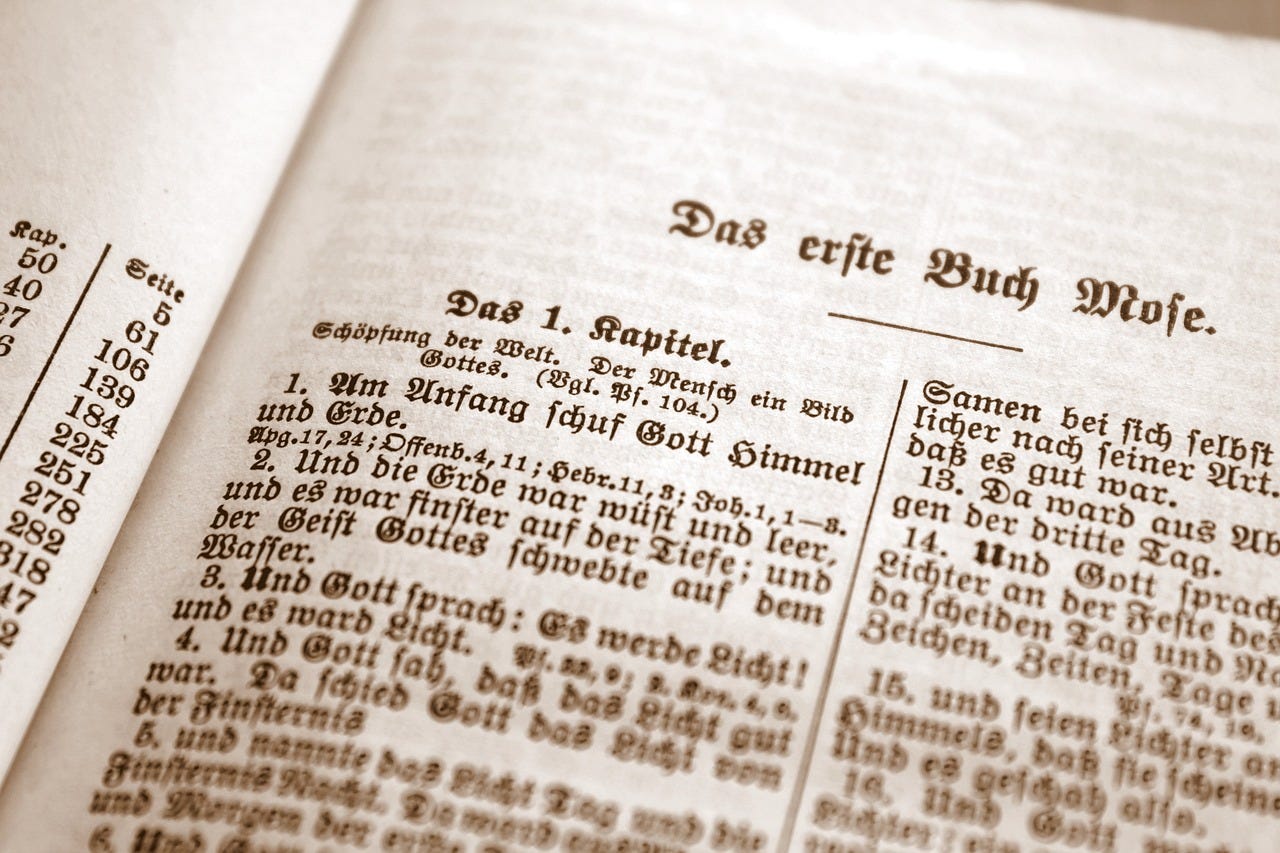

I probably don’t have to tell you that we live in an age when the very concept of truth is under threat. One of the most pervasive mantras of the current zeitgeist is “live your truth,” which, of course, implies that what is true for you may not be true for me, so we should just leave each other alone.1 Christianity, though, stands on the foundational belief that objective truth exists, meaning that truth is not found inside the individual person, but rather comes from some other, timeless source. That source for Christians, of course, is God, creator of all, and therefore the very standard of truth. If there is objective truth, then there is a reason to proclaim what is true to others, not in a haughty, threatening, or belittling way, but with the goal of love and unity.

When it comes to theology, or what we believe about God, there are objective truths and there are false beliefs. As Christians and as theologians, we should always be seeking the truth about God, our faith, and the Bible. But what are we to do when someone we thought was a fellow Christian expresses a belief that we are sure is false? Should all false beliefs be confronted the same way? And what if we are not sure what we believe about a certain theological point? Do we risk losing our salvation if we don’t hold the correct view on, say, infant baptism, the end times, or whether it’s possible to lose our salvation?

If we are going to study theology (and every disciple of Christ should study theology!), we need to understand a foundational concept called theological triage.

what is theological triage?

Imagine you went to the emergency room with a badly sprained ankle, and you had been waiting for a couple of hours. A nurse just told you that you are next in line, but suddenly, an ambulance pulls up, and paramedics wheel in a little girl on a gurney who has clearly just been in a bad accident. Are you still next in line? Of course not. As soon as that girl showed up in a much more dangerous situation than your sprained ankle, you got bumped back a spot. This happened because of a well-known medical practice called triage. When multiple patients are waiting for treatment, doctors and nurses know to assess the severity and urgency of each case before deciding who will be treated first. If the ER operated on a first-come, first-served basis, you might be getting your sprained ankle wrapped while that little girl lay dying. The practice of triage says that the more urgent case should be handled first, that way the girl is more likely to be saved.

A theologian named Albert Mohler, Jr. observed this practice during an actual ER visit, and realized that the same idea could be applied to the study of theology. “The same discipline that brings order to the hectic arena of the Emergency Room can also offer great assistance to Christians defending truth in the present age.”2 Not all theological ideas and disagreements, he realized, had the same level of importance. If we are to study theology (did I mention we should all be studying theology?), we need to be able to decide what theological ideas are essential to the Christian faith, what ideas are important but not necessarily essential, and what ideas are relatively unimportant.

Mohler proposed three “orders” of doctrines. First-order doctrines are those that are “most central and essential to the Christian faith.”3 A great example of a doctrine in this category would be the Trinity. Christians believe in one God in three persons: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. If you deny the doctrine of the Trinity, you are putting yourself outside of the historical Christian church. To say that a Jehovah’s Witness, who does not believe in the Trinity, is not a Christian is not a statement of condemnation, but simply a statement of categorical fact. Their beliefs fall outside of the essential beliefs of the Christian faith.

Second-order doctrines are those that believing Christians may disagree on, but such disagreement creates a significant theological boundary. Infant baptism vs. believer’s baptism is a second-order doctrine. Most Christians on both sides of this debate would agree that those on the other side are Christians. We’re all trying to carry out Christ’s command to baptize and make disciples, we just have very different interpretations of what that command entails. However, such a disagreement would make it hard for the two sides to be a part of the same congregation, since one of the fundamental practices of the church would be a point of disagreement.

Third-order doctrines are those that we can disagree on and still have close fellowship, even within the same local church. Two good friends of mine disagree on the subject of the rapture. One day, we’ll all know which one of them is wrong (it could be both!), but until then, they both realize that this particular doctrine is not one that should divide them.

why is theological triage important?

As we study theology, we face two opposite dangers: we may look at a doctrine and hold it as being more important than it actually is, or we may consider one that is important and think that it doesn’t really matter. For example, does the virgin birth of Jesus Christ hold a first-order importance, or is it something we can agree to disagree on?4 If your friend’s church has a different belief from yours on the practice of speaking in tongues, should you tell her that her soul is in mortal danger? If we are going to be able to effectively defend our faith, we need to know which doctrines are essential to that faith.

Mohler again gives an important example of why theological triage is so important. He points out that the fundamental problem with liberal Christianity is that they don’t see any doctrines as first order. “Liberals treat first-order doctrines as if they were merely third-order in importance, and doctrinal ambiguity is the inevitable result.” At the opposite extreme, though, Fundamentalists elevate all or most theological issues to the highest level. “Thus, third-order issues are raised to a first-order importance, and Christians are wrongly and harmfully divided.” Jesus, though, chastised the religious leaders for putting too great an emphasis on the little things, and neglecting what was really important: “Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For you tithe mint and dill and cumin, and have neglected the weightier matters of the law: justice and mercy and faithfulness. These you ought to have done, without neglecting the others.”5 Paul, writing to the Romans, warned them not to “quarrel over opinions,”6 implying that they were arguing over doctrines that didn’t really matter all that much and didn’t have a clear right or wrong.

Our goal in theology should always be truth, but we must balance that pursuit with an understanding of what is and what isn’t essential to the Christian faith. Otherwise we risk unnecessary disunity within the body of Christ.

If you would like to learn more about the concept of theological triage, I recommend the book “Finding the Right Hills to Die On,” by Gavin Ortlund. I greatly enjoyed the audiobook version, but I hope to give it a more thorough reading in the future.

Of course, in practice, Christians are often told they need to live everyone else’s truth, too, rather than what they believe, but this isn’t the place for that conversation.

R. Albert Mohler, Jr., “A Call for Theological Triage and Christian Maturity,” Albert Mohler (website), July 12, 2005, https://albertmohler.com/2005/07/12/a-call-for-theological-triage-and-christian-maturity.

Mohler, “A Call for Theological Triage and Christian Maturity.”

We’ll answer that question soon!

Matthew 23:23, ESV.

Romans 14:1, ESV.