“Lefty loosey, righty tighty.”

“If red touches yellow, you’re a dead fellow; if red touches black, you’re OK, Jack.”

“Honey catches more flies than vinegar.”

“Never get involved in a land war in Asia.”

We have lots of little, memorable sayings that help us remember a fact, truth, or idea that might come in handy from time to time. You can probably remember a few more off the top of your head. Humans have been memorizing important sayings and ideas since the beginning of recorded history. These sayings serve all kinds of purposes: farming, construction, social interactions.

And religious instruction.

When it comes to that last one, believers in the early church memorized a lot of Scripture to remember important ideas from the teachings of Jesus and his apostles. But they also found the need for sayings that helped them remember a set of important ideas that might not be found all in one place in the Scriptures. For this purpose, they developed sayings called creeds.

what is a creed?

A creed is, quite simply, a statement of faith, declaring a set of beliefs as succinctly as possible.1 A creed is an easy way to summarize the most important beliefs of a faith system, and as a result, they are easy to memorize and recite regularly, making them a great way to learn some basic (or sometimes not-so-basic) theology, as well as to confess what we believe as Christians. In liturgical churches, you’ll often hear a congregation recite a creed as a regular part of their Sunday-morning service.

Less liturgical churches rarely if ever use creeds in their worship services or in other teaching environments. In fact, some are outright opposed to the use of creeds. Michael Bird, in his book on the Apostles’ Creed, tells the story of a congregation in the Free Church tradition which proudly proclaimed on its church bulletin “No Creed but Christ, no book but the Bible.” Bird points out that this is, in fact, a sort of “anticreedal creed," a succinct statement proclaiming the exclusive roles of Christ and the Bible in their church.2 Creeds have been maligned by an association with mindless repetition, pointless theological jargon, and sometimes division in the church.3

That church is right, of course, to give Christ and the Bible exclusive roles in the life and mission of the church. No creed (unless it’s found in the Bible, see below) is on the same level as Holy Scripture. It was written by regular, fallible human beings, and they can contain mistakes. But the best creeds are based on Scripture, and distill the fundamental beliefs of scripture into something that can be very helpful. I’m a strong proponent of memorizing Scripture, and I would never suggest memorizing a creed instead of memorizing Scripture, but a creed can be a great tool alongside a strong scriptural knowledge.

But if you’ve been reading your Bible and memorizing Scripture, you may already know a few creeds! Let’s look at some creeds that can be found in the Good Book itself.

creeds in the Bible

One of the earliest creeds in Christian tradition is found way back in the book of Deuteronomy, and became known as the Shema: “Hear, O Israel: the Lord our God, the Lord is one. You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind.”4 In this passage, Moses goes on to tell the people of Israel to hold these words close to their hearts, teach them to their children, talk about them every day, write them on their doorposts and gates. This little statement was to be the cornerstone of their faith. When one rather important first-century Jewish rabbi was asked what commandment was the greatest, he answered by quoting this creed.5 Even today, devout Jews repeat this creed twice a day.

In the New Testament, we find several early statements of faith that can be categorized as creeds. The simplest is “Jesus is Lord”;6 anyone declaring this creed from their heart was regarded as a Christian.7 Paul gives a slightly more complex creed in his first letter to the Corinthians: “For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the Scriptures, and that he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve.”8 Notice that Paul says that these beliefs are of “first importance.” Sounds like Paul knew something about theological triage!

creeds in the early church

The pagan religions of the ancient Roman world didn’t have creeds. Their religions, for the most part, weren’t about truth. But Christianity, like Judaism before it, claimed that there was one God who had revealed himself to them. Christians believed that God’s truth was embodied in the person of Jesus; they needed a way to define what was true and what was not.9 “Only Christianity,” states Piotr Ashwin-Siejkowski, “from its very beginning called its faithful followers of Christ to confess a particular faith which was much more than just an emotional adherence to Jesus.”10

The early church developed their earliest creeds as simple statements of this faith, often pulled directly from the teachings of Paul and the other Apostles. Creeds were often composed in response to some heresy threatening the church or a doctrinal question that had arisen.11 The early church felt a need for these simple and memorable statements of belief.

the ecumenical creeds

Three creeds developed by the early church became known as the ecumenical12 creeds, because they were composed and agreed upon during a time when the eastern and western churches were more or less unified, and because even today they express the core beliefs that almost all Christian traditions agree upon. These are the Apostles’ Creed, the Nicene Creed, and the Athanasian Creed.

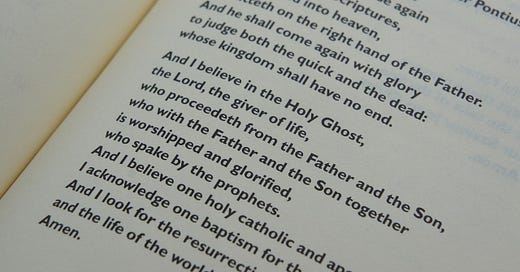

The first two of these creeds are still frequently confessed in churches around the world today, and they are interesting to compare as well, because they developed in rather different ways. The Apostles’ Creed developed somewhat organically “out of the inner life and practical needs of early Christianity,”13 and as a result is more basic and easier to memorize. The Nicene Creed, on the other hand, was composed and approved first at the Council of Nicaea in A.D. 325, and then expanded somewhat at the Council of Constantinople 56 years later.14 While the Apostles’ Creed grew organically, the Nicene Creed was created specifically to counter the Arian controversy, which questioned the nature of Christ. As a result, while both creeds affirm the Holy Trinity, the Nicene Creed goes into much greater detail on the divinity of Christ and the Holy Ghost.

what good are the creeds to us?

Well, before we answer that, let’s mention what the creeds are not. The creeds are not meant to be comprehensive statements of Christian faith. They do not include all of the doctrines of Christianity, nor even all of the most important doctrines. They were created for specific purposes, such as the Nicene Creed for the Arian controversy, and so they often emphasize doctrines that were most important in the context in which they were written. But that also doesn’t make them dated; after all, the same old heresies rear their ugly heads still today. Some churches have much longer doctrinal statements called catechisms that are much closer to being comprehensive, but because of this, they often include many beliefs that not all church traditions will agree on.15

As mentioned above, they also are not Scripture, and they are not divinely inspired in the way that Scripture is. Although the ecumenical creeds are affirmed by most church traditions, they are not infallible. And in fact, that means that we can create new creeds if we need a way to memorize other doctrines easily and quickly.

I believe that the creeds can serve two great purposes for the church today, even for non-liturgical churches. First, they form a foundation for sound Christian doctrine. If you want to study theology, the creeds are a great place to start. They give us most, if not all, of the most important doctrines of the Christian faith. Second, because of this, they are a great reminder that the beliefs that unite the church around the world today are more important than the things that divide us. If you walked into almost any Christian church in your city, you would find these doctrines. Sadly, in many churches they get little more than lip service, but they are there. Even in the Free Church that Michael Bird visited, they may reject the idea of creeds, but if you asked them about each of the doctrines found in the Apostles’ Creed, for instance, I can almost guarantee you that they’d affirm each one.

But I don’t want to just tell you these two great purposes of the creeds; I’d like to actually show you. So, next time, we’re going to dive into the Apostles’ Creed so that we can get a better idea of how it can help us learn both sound doctrine and Christian unity.

Read next:

the apostles' creed: part 1

Last time, we started looking at the creeds and their role in the church, both historically and today. This time, let’s dive into one of those creeds to understand where it came from and what it says about the Christian faith.

The word “creed” comes from the Latin word credo, which means “I believe,” and is the first word of both the Apostles’ and Nicene Creeds in Latin.

Michael Bird, What Christians Ought to Believe: An Introduction to Christian Doctrine Through the Apostles’ Creed (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2016), 17.

Bird, 18.

Deuteronomy 6:4-5, ESV.

Mark 12:29-30. It’s Jesus y’all, the rabbi is Jesus.

Romans 10:9; I Corinthians 12:3; 2 Corinthians 4:5; Philippians 2:11.

Alister McGrath, I Believe: Exploring the Apostles’ Creed (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1998), 11.

I Corinthians 15:3-5, ESV.

James C. Howell, The Life We Claim : The Apostles' Creed for Preaching, Teaching, and Worship (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2005), 9. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Piotr Ashwin-Siejkowski, The Apostles' Creed : And Its Early Christian Context (London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2009), ProQuest Ebook Central, 4.

Bird, 23.

Ecumenical means “promoting or tending toward worldwide Christian unity or cooperation,” according to Merriam-Webster.

Philip Schaff, The Creeds of Christendom: With a History and Critical Notes, Sixth Edition (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book house, 1877), 16.

Because of this, it is often called the “Nicaeno-Constantinopolitan Creed,” in case you wanted a name that was as challenging to memorize as the creed itself.

For a better understanding of catechisms, I recommend Alex Fogleman, “What is Catechesis?” Anglican Compass, March 6, 2018, https://anglicancompass.com/what-is-catechesis/.

One of the things we did at a previous church was recite creeds (mainly Apostles') during moments of "high church" ceremony. Times like baptisms, welcoming members into the church, certain important dates, etc. I sometimes miss that sense of corporate unity during those recitations. They are certainly great reminders of the unity of belief on the first importance items of the faith. Even as we look at Paul's letters to the various early churches, there are usually sections of those letters that read very much like creeds (e.g. Christ's preeminence in Colossians).

Looking forward to more on the specific creeds.

Read a book recently called “Habits of the Household” by Justin Whitmel Earley. He recommends using/creating family creeds for little children during significant moments of the day, like bedtime, as a way to transition, bring order, and add security.

It made me think about creeds differently.